Scenically

set in the southeastern part of the Colorado Plateau - a geographic

area that extends throughout the Four Corners region of the southwestern

United States – the Zuni Pueblo is surrounded by a spectacular

expanse of tablelands, mesas, cliffs, and canyons. The Zuni refer to

their Pueblo as Halona Idiwan’a, meaning“Our Middle Place.”

The Zuni culture is thought to be derived from both the Mogollon and

Ancestral Pueblo people – The Anasazis, who lived in the deserts

of New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, and southern Colorado for over two thousand

years.

The Zuni language is unique and spoken only by the Zuni people. However,

it has been influenced to some extent by languages from neighboring

tribes - Hopi, Keresan, Tanoan, Navajo and Pima. The native name for

Zuni is Shiwi or Shiwi'ma (the

Zuni way) and the Zuni call themselves A:shiwi. The name Zuni is adapted

from the Keresan Suni'tsi, meaning “unknown.”

Zuni legends have been handed down through the generations as stories

told by the elders. Zuni legends tell of a time when Children of the

Sun led their ancestors out of the underworld through four wombs of

earth searching for the center of the Universe – the Middle Place.

After many wanderings, they finally found the middle, called Hepatina,

where they built their first village, Itiwana. Zuni ancestors, according

to this legend, had reached the site of Halona, the present Zuni Pueblo.

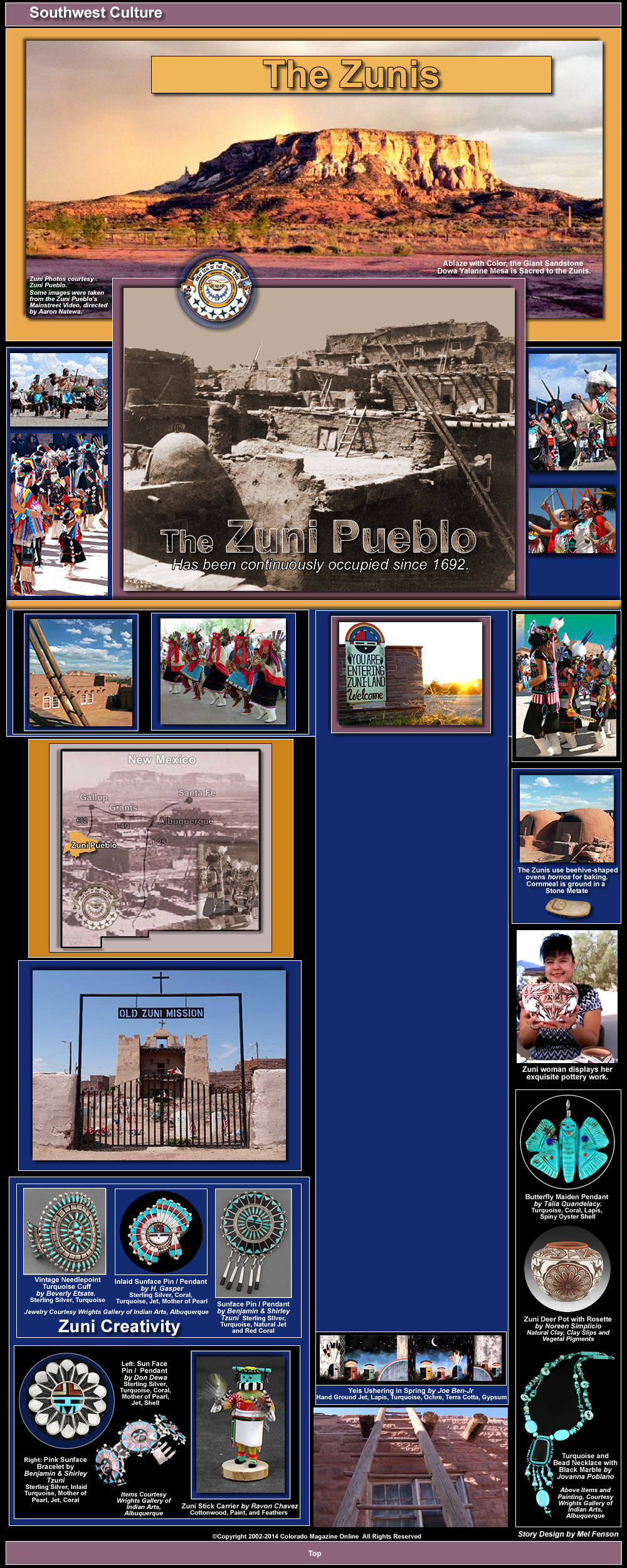

With a population of approximately 12,000 people, the present Zuni Pueblo is the largest of the nineteen Pueblos in New Mexico. It is built upon a small knoll on the north bank of the Zuni River, about three miles west of the towering Dowa Yalanne Mesa. Nearby rocky mesas and canyons probably served as quarries for the stone used in its construction. The Pueblo has been continuously occupied since 1692. Located in the northwestern part of the New Mexico, along its western border, the Zuni pueblo is about 35 miles south of Gallup, New Mexico and 150 miles west of Albuquerque. It extends over more than 700 square miles, covering 450,000 acres. Most of its residents live in the main village of Zuni and in the nearby community of Black Rock.

Traditional pueblo construction used limestone blocks or large adobe bricks made from clay and water measuring approximately 8 by 16 inches with a thickness of 4 to 6 inches. The structures were modeled after the cliff dwellings built by the Ancestral Pueblo (Anasazi) culture. Typical pueblo buildings were constructed as high as four or five stories tall. Within the Zuni Pueblo are courtyards and terraces. Defense was a key factor in the original architectural plan for the Pueblo. Rooms were accessed through openings in the roofs from ladders, which could be pulled up to prevent enemy access.

Zuni religious ceremonies are held in Kivas, which are square-shaped rooms - unlike the circular Kivas of many other pueblos. The Kivas are entered by a ladder through the ceiling. The Zuni Pueblo has six Kivas.

Zuni

is a sovereign, self-governed nation with its own constitutional government

led by a tribal council and a governor. The pueblo has its own courts,

police force, school system and economic base. The Pueblo has many Tribal

Programs, among which are an Environmental Protection Program, an Education

and Career Development Center, a Senior Citizen Center, a Wellness Center,

a Public Library, a Radio Station - KSHI (90.9 FM), a Tribal Records

& Archives Department, and a Youth Center. A tribal fairground and

government offices are built inside the Pueblo. The Pueblo's business

district has a mix of traditional and modern shops.

The ancient homelands of the Zunis, dating back several thousand years,

extended along the middle reaches of the Zuni River, a tributary of

the Little Colorado River. Approximately 90 miles long, the river has

its origin in Cibola County, New Mexico, at the Continental Divide.

It flows southwesterly through the Zuni Indian Reservation to join the

Little Colorado River in eastern Arizona.

The "Village of the Great Kiva" near the contemporary Zuni

Pueblo was built in the 11th century. By the 14th century, the Zuni

inhabited a dozen pueblos that had between 180 to 1,400 rooms. All of

these pueblos were abandoned by 1400. Over the next 200 years, nine

large new pueblos were constructed, but by 1650, there were only six

Zuni villages remaining. These were the Zuni villages witnessed by Coronado

and his men, who were lured to the Southwest in 1539 - drawn by the

myth of the Seven Cities of Cibola - in a quest for gold. With the exception

of the village of Zuni, all the early sites were abandoned long ago.

For the past three hundred years, since the early 1700s, most of the

Zuni have lived in the still existing Zuni Pueblo. However, today many

of the Zuni people live nearby in modern flat-roofed houses made from

adobe and concrete block. Beehive-shaped ovens (hornos) are still used

for baking at the Pueblo. Cornmeal for baking has been traditionally

ground in a stone metate.

Within the present day Zuni Pueblo’s boundaries are located the

small farming villages of Pescado, Nutria, and Ojo Caliente, which date

back to the eighteenth century. Today, they are occupied only during

planting and harvest seasons. Beyond the boundaries of the reservation,

are ancient sites and areas, sacred points and shrines, and places of

pilgrimage central to Zuni life and history.

It was the Zuni Pueblo where Europeans made their first contact with

the Native People of the Southwest, when in 1539 Friar Marcos de Niza

and a black Moorish former-slave named Estevanico led a party from Mexico

in search of gold and the fabled "Seven Cities of Cibola.”

Estevanico arrived at the ancestral Zuni village of Hawikku before Marcos,

but was killed in an ensuing dispute with the Zunis. Fray Marcos was

forced to retreat to Mexico without having actually seen the Pueblo,

however, upon his return to Mexico, he spread embellished but fictitious

stories about the fabled cities of gold they had found. Perhaps what

he had seen was the late afternoon sun reflecting on the walls of the

village of Hawikku, which gave an appearance of gold.

Before the Spanish came, Mexican Indians had long traded with the Zuni,

exchanging shells and tropical bird feathers for salt, turquoise and

red paint. The Indian traders knew what the Spanish thought were the

Cities of Cibola were actually small adobe villages.

Friar Marcos' tales of riches enticed Francisco Vasquez de Coronado

to mount a full scale expedition to explore and claim the fabled lands

of Cibola for Spain. A year later on July 7, 1540, Coronado reached

Hawikku with a force of men 2,500 strong that included several hundred

Spaniards and a couple of thousand Amigos Indios, who were the Mexican

Indian allies of the Spanish. After a battle with the Spaniards and

their Indian allies, the vastly outnumbered Hawikku warriors withdrew

under the cover of night. They later returned to their homes and co-existed

with the Spanish, who remained in the area for several months before

continuing eastward in search of more lands to claim for Spain. Coronado

returned to Mexico in 1542 with the truth about the cities of Cibola.

It was, however, forty-three years later before the Spanish returned

to establish missions at some of the Zuni villages.

In 1680, agitated by the harsh treatment of the Indians by the Spanish,

all the Pueblos in New Mexico, including Zuni, joined in a Pueblo uprising

to plan and carry out a coordinated revolt against Spanish domination.

After attacking and burning the Spanish mission at Halona Idiwan'a,

the people of all six ancestral Zuni villages sought defensible refuge

on the nearby sacred, Dowa Yalanne, a steep mesa southeast of the Zuni

Pueblo. (Dowa means corn and Yalanne means mountain.) They remained

in a defensive position on the mesa until 1692, when the Spanish made

peace with the Pueblos. The Zuni people then returned from the mesa

and consolidated into a single Pueblo at Halona Idiwan'a, which is the

present-day Zuni Pueblo. Although at peace with the Spanish, the Zuni

Pueblo still faced raids by the Apaches, Navajos, and Plains Indians.

After the Mexican territories gained independence from Spain in 1821,

the Zuni Pueblo, along with the rest of New Mexico, became part of the

Republic of Mexico.

Following the Mexican-American War, New Mexico, including the Zuni Pueblo

became a United States Territory in 1848. The Zuni reservation was officially

recognized by the United States federal government in 1877. New Mexico

gained statehood in 1912.

Frank Hamilton Cushing, a pioneering anthropologist and ethnologist

associated with the Smithsonian Institution, lived with the Zuni from

1879 to 1884. He was one of the first participant observers of their

culture. He studied and wrote extensively about Zuni life and culture.

He learned their language and their customs and even dressed in native

attire. In 1881 Cushing was initiated into the Zuni warrior society,

the Priesthood of the Bow and received the Zuni name Tenatsali,

"medicine flower." The Bow Priesthood was thought to have

obtained its power from the twin War Gods who led the Zuni out of the

Earth in ancient times. In 1882 Cushing took his Zuni father and fellow

Bow members on a tour of the Eastern United States, where they met President

Chester Arthur and attracted considerable media attention.

Although

responsible for the Pueblo's defense and keeping order in the villages,

the Priesthood of the Bow also dealt with Zuni witches, who were thought

to possess supernatural or magical knowledge and could cast evil spells

or cause harm to people in the Pueblo. Bow Priests conducted trials

of people accused of witchcraft or other crimes and sometimes performed

executions of people judged to be guilty.

Unfortunately, continual appropriation and abuse of Zuni lands by the

U.S. Government and unscrupulous land grabbers led to the gradual shrinkage

of the Zuni's original territories and the Zuni eventually became constrained

to a reservation that was only a fraction of its original size. Following

years of negotiation with the U.S. Government, the Zunis finally won

a $25 Million settlement as compensation for land taken from them.

Throughout the year, the Zunis hold traditional ceremonial celebrations.

Tribal dancers perform in plazas within the Pueblo. Visitors to the

Zuni Pueblo are allowed to witness some of the Zuni dances and ceremonies.

The most sacred Zuni event is the annual Sha'lak'o festival, which is

a winter solstice celebration held annually by the Zuni Pueblo. The

celebration includes Sha'lak'o dancers who purify and bless Mother Earth,

the people, and the community. Zuni religious beliefs are based on the

three powerful deities: Earth Mother, Sun Father, and Moonlight-Giving

Mother, as well as Old Lady Salt, White Shell Woman, and other Kachinas.

Katchinas are deified ancestral spirits impersonated in religious rituals

by masked dancers. Other Zuni ceremonies celebrate the passage of certain

life milestones that include birth, coming of age, marriage and death.

Every four years the Zuni make a religious pilgrimage to Kachina Village

about 60 miles southwest of Zuni Pueblo on the Zuni Reservation. The

four-day observance occurs around the summer solstice. Another pilgrimage

conducted annually is made to the Zuni Salt Lake, home to the Salt Mother.

Here the Zuni harvest salt and celebrate religious ceremonies. Other

events held throughout the year include the Zuni Tribal Fair and rodeo,

which is held the third weekend in August. The Zuni also participate

in the Gallup Inter-Tribal Ceremonial that is usually held in early

or mid-August.

The Zuni livelihood has traditionally been based on irrigated farming

with the growing of corn, squash, pinto beans, wheat, chili, cabbage,

onions and beets, and the raising of livestock. Much of Zuni ceremonial

ritual centers the production of crops. Over time the Zuni began to

farm less and concentrate more on raising sheep and cattle as a means

of economic growth. Their success as a desert agri-economy is based

on careful management and conservation of resources. Some Zunis also

work in nearby towns, particularly in Gallup.

Many contemporary Zuni also rely on the sale of traditional arts and

crafts as a source of income. The Zuni are noted for their excellent

artistic work, which includes paintings, silversmithing, needlepoint

work, and pottery making. They also create fetishes, which are representative

images of deities made of wood and decorated with paint and feathers.

The Zuni silversmithing began in the 1870s, after they learned fundamental

silver-working techniques from the Navajo. By 1880, Zuni jewelers learned

to create intricate designs and unique patterns by inlaying turquoise

in silver, to create jewelry, such as necklaces, bracelets and rings.

They also do inlay work, using mother-of-pearl and coral. Many Zunis

are master silversmiths. Silversmiths sell their jewelry to traders

in Gallup, Santa Fe, Albuquerque and other cities.

Zuni

women have traditionally made pottery for food and water storage. They

decorate the bowls, jugs and vases with symbols of their clans. Clay

for the

pottery ,which is found locally, is ground, then sifted and mixed with

water. It is then rolled into a coil and shaped into a vessel or other

design, then scraped smooth with a scraper. A thin layer of finer clay,

called slip, is next applied to the surface for extra smoothness and

color. The vessel is polished with a stone after it dries. Images are

then painted on the pottery with home-made organic dyes, using a traditional

yucca brush. In the past, the Zuni used animal dung in traditional kilns

to fire the pottery. Today Zuni potters sometimes use electric kilns.

The Zuni have always had maps. The Zuni Map Art Exhibition is a project

developed and produced in partnership with the A:shiwi A:wan Museum

and Heritage Center in Zuni, New Mexico. It is a collection of Zuni

map art paintings that illustrate ancestral Zuni sites throughout the

Colorado Plateau and depict it as a cultural and sacred landscape. The

paintings were created by 14 Zuni artists in collaboration with Zuni

cultural advisors.

Although Zuni life continues today, honoring its ancient traditions and culture, its people have also adopted modern day technology, such as cell phones, microwave ovens, computers and the Internet – to keep pace with the ever evolving lifestyles of today's world.

For

more information, visit:

www.zunitourism.com

Edited

by Mel Fenson from information obtained from web sources and from:

“The Zunis of Cibola”

by C. Gregory Crampton,

“The Zuni” by Nancy Bonvillain, “Treasures of the

Zuni” by Theda Bassman, and "New Mexico" published by

the

University of New Mexico Press.

Special

Thanks to Wrights Gallery of Native American Arts, Albuquerque, New

Mexico for providing images of Zuni arts and crafts.

www.wrightsgallery.com