Shrouded

in a mystery of lost gold, storied Victorio Peak is a craggy outcropping

of rock that rises 5,499 feet from the center of a dry desert lake known

as the Hembrillo Basin. It lies in Dona Ana County in southern New Mexico’s

San Andres Mountains.

Originally, ancient hunters many thousands of years ago may have stumbled

upon Victorio Peak and discovered the fissures and caves in the worn

granite cliffs that top the peak. Inside this catacomb of volcanic caverns

was a natural shaft that led steeply down to an underground river.

Eventually, with reputed veins of gold inside the caves and placer gold along the banks of the underground river, the site may have been mined by the Olmecs as early as 1300 BC and later by the Toltecs, Hohokam, and Aztecs.

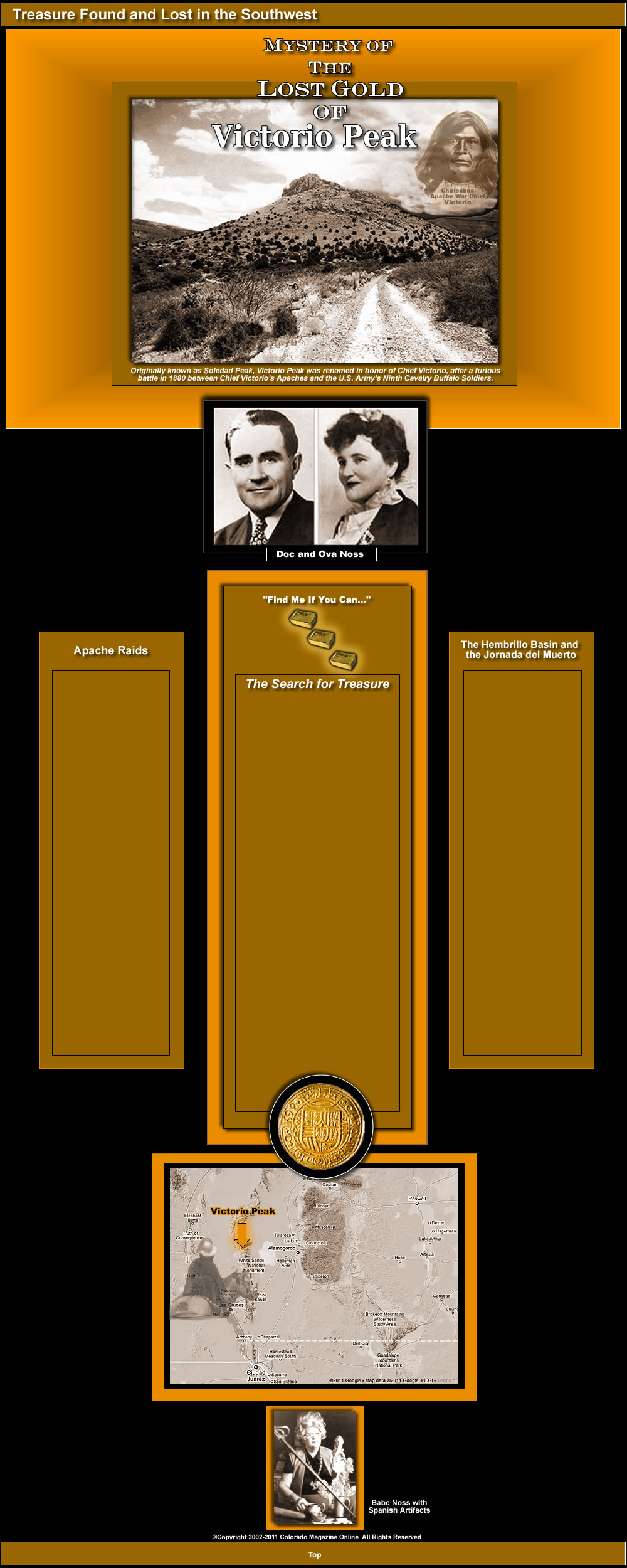

In 1937, a gold prospector named, Milton Ernest "Doc" Noss claimed to have found an enormous treasure cache deep within Victorio Peak’s hidden passages.

Doc Noss, who was said to be part Indian, was born in Oklahoma and had traveled all over the Southwest seeking excitement. In 1933, he married Ova "Babe" Beckworth and the two settled down in Hot Springs, New Mexico - later known as Truth or Consequences.

In November 1937, Doc, Babe, and four others left on a deer hunt into the Hembrillo Basin. Setting up camp on the desert floor at the base of Victoria Peak, the men headed into the wilderness, while their wives stayed at camp. Hunting by himself, Doc scouted the base of the mountain. When it began to rain, he sought shelter under a rocky overhang near the summit of the mountain. While waiting for the rain to subside he noticed a large rock that looked as if it had been dislodged. Curious, he struggled with it and managed to move it aside. To his surprise, he discovered a hidden tunnel that descended into the mountain.

Peering into the darkness, Doc was able to discern an old shaft to which a thick, wooden pole was attached at one side. He thought he had discovered an abandoned mineshaft. When the rain finally stopped, Doc returned to camp and told Babe about his discovery. The two decided to keep the discovery between themselves and return to the inspect the shaft later.

A few days later, Doc and Babe

returned to the site, bringing ropes and flashlights. Distrusting the

old wooden pole attached to the side of the passage, Doc climbed into

the shaft using a rope. While Babe waited at the top, Doc inched his

way nearly sixty feet down the narrow passageway into the mountain.

Upon reaching the bottom - as Doc reportedly related his story - he

entered a chamber, which was the size of a small room. On the walls

he found drawings that appeared to have been made by Indians. Some were

painted and others chiseled into the walls. At one end of the chamber,

the shaft continued downward. Once again, Doc climbed down another 125

feet, to where the shaft leveled off into a large natural cavern. He

found several adjoining smaller rooms that had been chiseled from the

rock along one wall. Stepping into an eerie darkness, Doc was alarmed

when he spotted a human skeleton with its hands bound behind its back.

It was in a kneeling position and securely tied to a stake driven into

the ground. Within moments he discovered more skeletons - most of them

bound and secured to stakes like the first. As he explored further,

he found more skeletons stacked in a small enclosure, much like a burial

chamber. In all, he reportedly found twenty-seven human skeletons in

the caverns of the mountain.

As he continued to explore the side caverns, Doc claimed he found a hoard of treasure including coins, jewels, saddles and priceless artifacts, including a gold statue of the Virgin Mary and some old letters - the most recent was dated 1880.

This treasure was only the beginning. In a deeper cavern, Doc found what he thought was a stack of worthless black iron bars. He estimated there were thousands of these bars stacked against a wall, each he estimated, probably weighed over forty pounds.

Doc filled his pockets with gold coins, grabbed a couple of jeweled swords, and laboriously climbed back up the rope to Babe, who was waiting anxiously at the surface. After telling her what he had discovered and showing her what he had brought to the surface, she insisted that he go back into the mine for one of the iron bars. He once again climbed down into the forbidding darkness of the caverns and after much searching, finally found a small iron bar that was light enough to carry back through the narrow passageway. When he reached the surface, he told Babe, "This is the last one of them babies I'm gonna bring out." When Babe rolled the bar over, she saw a yellow gleam where the gravel of the hillside had scratched off centuries of black grime. To the Noses surprise, what looked like a piece of iron turned out to be a solid gold bar! Later, the value of the gold he had discovered in the cave was estimated to be worth more than two billion dollars.

After the discovery of the treasure, Doc and Babe spent every free moment exploring the tunnels inside the mountain, while living in a tent at the base of the peak. On each trip, Doc would retrieve two gold bars and as many artifacts as he could carry. At one time, as legend has it, he brought out a crown, which contained two hundred forty-three diamonds and one pigeon-blood ruby. Since Doc trusted no one, not even his wife Babe, he would disappear into the desert to hide pieces of the treasure in places that he never revealed to anyone.

Among the artifacts Doc said he retrieved, were some documents dated 1797, which he buried in the desert in a Wells Fargo chest from the caverns, along with various other treasures. Although the originals have never been recovered, it has been reported that a copy of one of the documents proved to be a translation from Pope Pius III.

Doc Noss cared little about the historical value of the treasures inside Victorio Peak. He mostly ignored the pouches, packs and artifacts scattered about, while he focused his attention on the gold coins and bars he found.

Unfortunately, Doc was unable to profit from the gold bars, because ironically, four years before his discovery, Congress had passed the Gold Act, which outlawed the private ownership of gold. Even though he was unable to sell the gold bars on the open market, Noss continued to work steadily at removing the treasure, hoping to sell it on the black market.

In the spring of 1938, Doc Noss and Babe went to Santa Fe to establish legal ownership of his find. He filed a lease with the State of New Mexico for the entire section of land surrounding Victorio Peak. He also filed several mining claims on and around Victorio Peak, as well as a treasure trove claim. With legal ownership established, Noss began to openly work his claim, but he also became increasingly paranoid, continuing to hide his gold bars all over the desert.

When Doc's story eventually hit the headlines, there was much speculation about the source of the treasure stashed inside Victorio Peak.

Did some of the treasure trace back to loot the Apaches had hidden, after their raids on travelers in the Jornada del Muerto?

Was it gold stolen from the Aztecs by the Spaniards?

In the Socorro-Hot Springs-Hatch area near White Sands and Victorio Peak, there is a local legend about the Casa del Cueva de Oro, or the “House of the Golden Cave.” Could this Golden Cave have been the gold mine in Victorio Peak? Some believe it was.

Others believe that Noss found the treasure of Don Juan de Oñate y Salazar (1550 – 1626), who founded New Mexico as a Spanish colony in 1598 and became its first colonial governor. During his rule, he reportedly amassed a treasure of gold, silver and jewels, before being ordered back to Mexico City in 1607.

There is also speculation that the treasure could be the missing wealth of Emperor Maxmillian, who was Mexico's emperor in the 1860's. When Maxmillian heard of a plot to assassinate him, he began to move his gold and treasures out of Mexico. According to legend, he sent a palace full of valuables to the United States to be hidden. Maxmillian was assassinated in 1867.

Some researchers theorized that the shaft could be the one mined by a Catholic missionary named Felipe La Rue, in the late 1800's, then used again later by Chief Victorio to store his plunder.

Padre La Rue, a native of France, was among the small group of priests who volunteered for service in Mexico. His party sailed to Florida, crossed the Gulf of Mexico to Vera Cruz, and from there, traveled to Mexico City by ox cart. From there they traveled north to the city of Chihuahua, which they reached in 1798. At the Padre’s new station in a large hacienda, he began his missionary work among the local Indians and Mexicans.

While there, he heard stories about a fabulous source of rich minerals in the mountains further to the north. Among his parishioners was an old man, who had been an explorer and soldier of fortune, during his youth, and had traveled widely over the country that lay to the north. Padre La Rue personally cared for the ailing old man and the two became good friends. One day, Padre La Rue asked him about the riches he had heard about. The old man told the priest he knew about a rich deposit of gold located high in the mountains about two days travel north of El Paso del Norte - the present-day site of El Paso, Texas.

Padre La Rue retraced a route to the peak based on information obtained from the old man and did locate a rich vein of gold. The priest and his followers worked the mine for years and formed the gold into bars. All the gold, except that which was needed for supplies was stacked along one wall of a natural cavern inside the mountain.

Eventually, Spanish soldiers were dispatched from Mexico with orders to locate the missing priest. When a small group of the Padre’s people were purchasing supplies in La Mesilla, near El Paso, they heard that Mexican soldiers were in the area searching for them. Hurrying back to their camp, they spread the alarm.

Padre La Rue immediately set about hiding all traces of the mine and he instructed his people to conceal the entrance. When the soldiers finally arrived and demanded to know where the gold, which was used to purchase the supplies in La Mesilla came from, Padre La Rue refused to answer. He died under torture, as did many of his followers. Although the soldiers searched for evidence of a mine, they returned to Mexico City without finding it.

The memory of the Lost Padre Mine, as it has since been called, remained only as a legend, until Doc Noss discovered the hidden passage on Victorio Peak that led to what might have been Padre La Rue’s gold.

In the Fall of 1939, Doc wanted to enlarge the passageway into Victorio Peak so the treasure could be more easily removed. He hired a mining engineer named, S.E. Montgomery, who suggested using eight sticks of dynamite to expand the tunnel’s opening. Noss strongly disagreed with this idea, claiming the mountain was too unstable to employ that method. However, the engineer convinced Noss to let him go ahead and use dynamite. Unfortunately, the dynamite blast resulted in a disaster. It caused a cave-in which totally collapsed the entrance to the fragile shafts. This turn of events made it impossible for Doc Noss to enter the cave to reach his treasure cache.

Doc tried several times to regain entry into the shaft, but the dynamite blast had left it sealed off with tons of debris. All of his attempts failed, leaving him an angry and embittered man. Now, instead of having thousands of gold bars to draw from, Noss had only a few hundred that he had hidden in the desert. When he later became desperate for cash, Doc along with a man named Joseph Andregg, unearthed and transported his remaining gold bars, coins, jewels, and artifacts into Arizona, and attempted to sell them on the black market. For nine years, Doc tried to sell his gold illegally, but it was difficult to find buyers.

This bad luck also caused problems in his marriage. He soon deserted Babe and in November 1945, his divorce was granted. Two years later, he married Violet Lena Boles, which further complicated the ownership of the rights of his treasure for years to come.

In the late 1940’s, according to unclear information, Doc had met an oil man named Charley Ryan from Alice, Texas. They made an agreement that Noss would sell some of his gold bars to Ryan for $25,000 in cash, which he would use to buy digging equipment to reopen the mine - with Ryan’s help. Before the deal was closed, Doc sensed a double-cross by Ryan. He dug up the gold that was to be used in the transaction and reburied it in place where Ryan could not find it. On March 5, 1949, Ryan arrived at the site and insisted on finding out what happened to the gold. However, Noss demanded to see the money before revealing the new hiding place. Ryan hinted that if Noss did not reveal the whereabouts of the gold, he would not live to enjoy it. An intense argument ensued and Noss headed toward his pickup. Ryan claims he feared Doc was going after a gun and fired a warning shot in his direction, demanding that Noss back away from the vehicle. Noss refused to obey and Ryan fired again, hitting Noss in the head, killing him instantly. Just twelve years after discovering the treasure, Doc Noss died with only $2.16 in his pocket. Ryan was charged with murder, but was later acquitted.

Meanwhile, Babe Noss had filed a counter-claim on the entire area, but was denied entry by the courts until legalities could determine the actual owner of the mine.

As the years passed Babe Noss held onto her claim at Victorio Peak. Occasionally she hired men to try to clear the shaft. In 1955, the White Sands Missile Range unexpectedly expanded its operations to encompass the Hembrillo Basin, including Victorio Peak. Babe was no longer allowed to enter the area. She began a regular correspondence with the military, requesting permission to work her claim, but she was always denied. After that, every attempt of Babe's to clear the rubble from the plugged shaft was met with a military escort out of the area.

This was the beginning of long legal battles over the ownership of the claim. A military claim to the area stemmed from a ruling made by New Mexico officials on November 14, 1951 that withdrew public prospecting rights and reserved the land for military use only. However, in dispute of the military’s mining claim, New Mexico officials stated they had leased only the land’s surface to the military and not any mining rights. Furthermore, they challenged that any underground wealth, in whatever form it existed, belonged to the state or to any legal license holders.

As the state’s legal actions became more involved, a search of mining records curiously failed to turn up any existing claims - including that of Doc Noss. A fact was also brought to light that the land where Victorio Peak is located was not even owned by the State of New Mexico, but was part of a ranch owned by a man named Roy Henderson, who had leased it to the Army.

The dispute was finally worked out when a federal court issued a compromise of sorts that stated the Army would be allowed to continue to use the surface of the land, but no one else would be allowed on the property without the Army's consent.

Even though the military refused any of Babe's efforts to work her claim, it apparently did not refuse other military personnel from exploring Victorio Peak. Two airmen from nearby Holloman Air Force Base, who were allowed access, claimed they had found another entrance to the caverns from a natural opening on one side of the peak. Airman First Class Thomas Berlett and Captain Leonard V. Fiege, said they had found approximately one hundred gold bars weighing between forty and eighty pounds each in a small cavern in Victorio Peak. After the discovery, Fiege told several people that he had caved in the roof and walls to make it look as if the tunnel ended.

Following their discovery, Fiege went to the Judge Advocate's Office at Holloman Air Force Base to confer with Colonel Sigmund I. Gasiewicz about their rights to the gold. Now two military commands had become involved in the gold rights dispute.

Berlett and Fiege formed a corporation to protect their interest in the gold they had found, and filed a formal application to enter the White Sands Missle Range for search and retrieval of the gold. However, the military issued an edict which forbid them to return to the site on the base.

In the summer of 1961, upon the advice of the Director of the US Mint, Major General John Shinkle of the White Sands Missile Range, allowed Captain Fiege and his associates to once again work their claim. On August 5, Fiege and his party returned to Victorio Peak, accompanied by the commander of the Missile Range, a secret service agent, and fourteen military police. However, Captain Fiege was unable to penetrate the opening he had used three years earlier. General Shinkle finally grew intolerant of the situation and ordered everyone out of the site.

Later, Fiege was again allowed back on the missile range to join a full-scale mining operation conducted by the military at Victorio Peak.

Fueled by suspicions that the military was working her claim, Babe Noss hired four men to surreptitiously enter the range. Though they were caught trespassing and escorted from the area, the men reported sighting the military’s mining operations to Babe.

Babe contacted Oscar Jordan with the New Mexico State Land Office, who in turn, contacted the Judge Advocate's Office at White Sands. In December 1961, General Shinkle shut down the military operation and excluded anyone from entering the base, who was not directly engaged in missile research activities.

In 1963, the Gaddis Mining Company of Denver, Colorado, under a contract with the Denver Mint and the Museum of New Mexico, obtained permission to work the site. For three months beginning on June 20, 1963, the group used a variety of engineering techniques to search the area, however, they failed to find any treasure.

In 1972, F. Lee Bailey, became involved in the dispute, representing some fifty clients including Babe Noss, the Fiege group, Violet Noss Yancy, Expeditions Unlimited - a Florida based treasure hunting group, and others. Reaching a compromise, the military base allowed Expeditions Unlimited, representing all of the claimants, to excavate the peak in 1977. However, the Army placed a two-week time limit on the group’s project and they had hardly started before they were forced to leave without finding anything. The Army then shut down all operations stating that no additional searches would be allowed.

Babe died In 1979 without ever finding the treasure. However, Terry Delonas, her grandson, continued the family tradition and formed the Ova Noss Family Partnership. By this time, Babe's story had spread across the nation with stories published in several magazines and newspapers.

Learning about the story, a man named Captain Swanner, who had been stationed at White Sands Missile Range in the early 1960's came forward. Speaking to a Noss family member, he stated that he had been the Chief of Security there in 1961 and had been sent to inspect the report made by Airman Berlett and Captain Fierge. After Swanner determined the accuracy of the two airmen’s report, the entire area was placed off-limits until a full official investigation could be conducted.

Although the military later confirmed that Swanner had served at White Sands during this time, they denied that there were any documents that supported his claim about the investigation.

Reportedly, the military eventually initiated another mining project and was able to penetrate one of the caves and inventory its contents. Then, according to unknown sources, the military supposedly removed the gold from the cave and sent it to Fort Knox. If it was actually sent there, there would be records certifying it was. Do any such records exist?

There were also unconfirmed rumors that members of the Nixon administration (1969 to 1974) may have been involved in the removal of the Victorio Peak gold. If so, to what destination did they transport the gold?

Today, Army's official position on the whereabouts of the gold remains evasive, maintaining that the burden of proof rests with the accusers.

Following Babe’s death, her heirs continued their effort to obtain permission from the military to excavate the peak, although many members of the Noss family and friends believe that the military exploited Babe's claim and that the treasure is now gone. However, Terry Delongas stated, "We're not accusing the military of stealing the gold, but I do feel that the Department of the Army in the 1960's treated my grandmother unfairly. “We've worked very hard over the years,” he stated, “to establish a working relationship with the military, and we're certainly not going to jeopardize that by accusing them of theft."

Their continuing effort paid off , when in 1989 a special act of Congress gave Terry Delonas and the other Noss family heirs permission to again investigate the site. However, as of 1995, no treasure had been found, but the Noss family has still not given up their quest for the gold.

The real truth about what happened to the treasure hidden in Victorio Peak will probably never be known, but there is no doubt that it existed because of the evidence that indicates it did, such as, photographs, affidavits and relics that are still held by the Noss family.

Edited

by Mel Fenson from

information obtained

from

Web sources.