Chief Niwot (The Arapaho name for Left Hand) was a tribal leader of the Southern Arapaho people, who had lived and hunted in Colorado, Wyoming, Nebraska, and Kansas since the 1700s. They often wintered in what is now known as Boulder Valley, where Boulder, Colorado would be established in the future. Chief Niwot, born in 1825, reputedly lived only until the age of 39, when he was thought to have died at the hands of the Third Colorado Cavalry, during the infamous Sand Creek Massacre in 1864.

A remarkable individual, Chief Niwot was a brave warrior and an intelligent leader, who tried to establish and maintain peaceful relations between his people and the white man. He learned to speak English at an early age, taught by his sister's husband, a trapper named John Poisal. This ability enabled him to better communicate with white leaders.

Niwot was one of the few Plains Indians who learned other tribal languages. He became fluent in both Cheyenne and Sioux languages. Most tribes communicated with one another in sign language.

The Arapaho Indians had originally been a sedentary, agricultural people living in villages in Minnesota. Their mother tribe had been the Algonquins. European expansion forced them westward. As they migrated west, their ways changed to a nomadic life, hunting buffalo, elk and deer. Their diet also included fish and food harvested from various plants and berries. They lived in buffalo hide teepees that could be easily erected and moved as they migrated west to follow the great buffalo herds.

A spiritual people, the Arapaho believe in an overall creator they call Be He Teiht. The Arapahos lived together in small bands of related family members. Once a year all of the bands of Arapaho congregated together for the Sun Dance festival, a seven day event held during the Summer Solstice. The Sun Dance was a time of prayer and sacrifice to the powers above. The festival preceded the great summer buffalo hunt. Still practiced by the Arapahos, it is now held only on the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming. Many Southern Arapahos from Oklahoma come to Wyoming every summer to attend the festival and to visit relatives in the north.

The Arapaho also practiced the Ghost Dance religion, which became popular in the1880s. Feared by the white man, the Ghost Dance prophesied that it would incite a great apocalypse and ultimately lead to a peaceful end of white American expansion, the preservation of the Native American culture, and the return of the buffalo.

Although

the Arapaho became close allies of the Cheyenne and eventually made

peace with the Sioux, Kiowa, and Comanche, they remained at war with

the Shoshone, Ute, and Pawnee tribes.

The Plains Arapaho eventually split into two separate tribes, the northern

and southern Arapaho. The northern Arapaho lived along the foothills

of the mountains at the headwaters of the Platte River in what is now

Nebraska, while the southern Arapaho moved toward the Arkansas River

Valley in what is now Colorado.

Although the Arapahos initially maintained friendly relations with the white man and traded with him, the growing western expansion of white settlers forced the Arapaho and other Plains Indians to move further and further west. In the meantime, the buffalo, upon which their existence depended, were being killed off by the thousands by white hunters who took their hides and left their carcasses to rot on the prairie.

In 1851, The Fort Laramie Treaty was signed between the U.S. Government and the Northern Arapaho, the Cheyenne and other tribes. It granted the tribes land in Wyoming, Colorado and parts of western Kansas and Nebraska, but the Pike's Peak Gold Rush of 1858 brought more white men into the west and the treaty was broken by the failure of the United States to prevent the mass emigration of settlers and miners during that period.

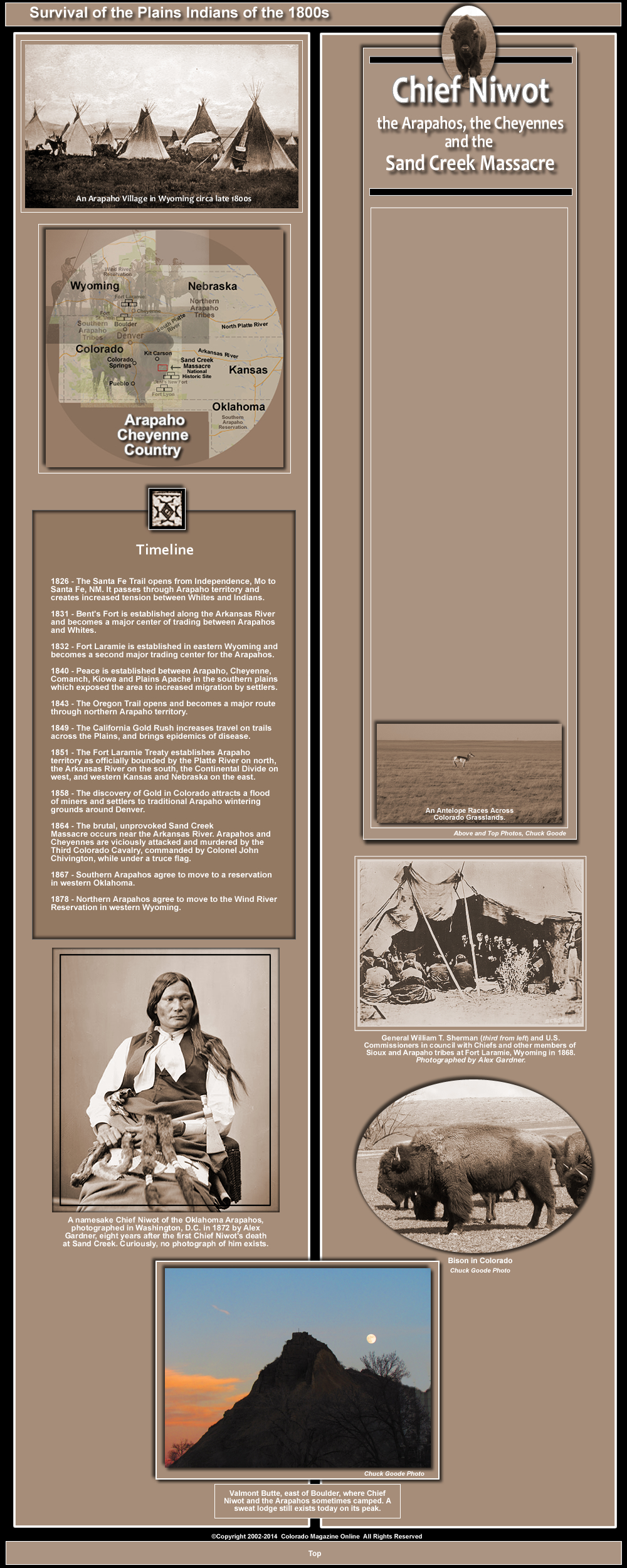

According to legend, Chief Niwot’s first encounter with gold prospectors in Colorado was when a group led by Captain Thomas Aikins, from Fort St. Vrain, 30 miles to the east, set up a camp near Valmont Butte, where Niwot and his deputies Bear Head and Many Whips were camped. The butte is just east of where Boulder is now located. Chief Niwot rode to meet them with a peaceful greeting but told him and his party to leave the area. When they refused, he threatened them.

After several tense days, with the threat of a battle hanging in the air, Niwot rode into Aikins’ camp once more. One of the Arapaho shamans, he told the Captain, had received a dream from the Great Spirit the night before. In the dream, the holy man envisioned a great flood covering the earth and swallowing the Arapahos, while the whites survived. Niwot interpreted the shaman’s vision to mean that gold seekers would flood his homeland and he could do nothing to stop them. Niwot realized that peace with the whites was the only way his people would avoid being swept away by the flood, so he and his neighboring chief, Little Raven, attempted to maintain a peaceful coexistence with the whites.

Peaceful relations, however, did not last. As whites continued to encroach on Arapaho land, a rash of settlements were established along the Front Range.

Then an 1862 Sioux uprising in the northern plains states made frontier settlements like Boulder jittery and the settlers became suspicious of the Arapahos, whom they had thought were friends. The Sioux Uprising had broken out between the Sioux - also known as eastern Dakota - and the United States Army as a result of treaty violations by the United States and late or unfair annuity payments by Indian agents that had caused increasing hunger and hardship among the Dakota.

By 1864, tension between whites and Arapaho warriors was high. Raids by tribes other than Niwot's on wagon trains and outlying settlements intensified. The brutal murder of the Hungate family on their ranch 25 miles southeast of Denver on June 11 caused the Territorial Governor John Evans, to believe that all the Native tribes were equally responsible. He decided to be rid of the "Indian problem" once and for all and ordered the peaceful Arapaho and Cheyenne to relocate to a area north of Fort Lyons on Sand Creek, which was in a remote part of the eastern Colorado plains. Governor Evans then ordered the Third Colorado Cavalry, commanded by Colonel John Chivington to patrol the prairies for hostile Indians.

Chief Niwot, along with Chiefs Little Raven and Black Kettle did as they were told. They camped peacefully at Sand Creek and continued not to make war on their white neighbors.

After months of patrolling, Chivington and the Third Colorado failed to find any hostile Native tribes on the prairie. In frustration, they headed for Sand Creek. Despite the fact that Major Edward Wynkoop, the commander of Fort Lyons, had stated that the Native people at Sand Creek had not been raiding, Colonel Chivington and his men viciously attacked the Arapaho encampment at dawn on November 29, 1864, completely surprising the sleeping Indian families. Chief Black Kettle was sure there was a mistake, and hastily raised both a U.S. flag and a white flag of surrender. His act of peace did not deter the brutal attack on his people and he was killed by the Calvary, which encircled the Indians’ camp and even directed canon fire on the defenseless people from a nearby hill. Bodies of dead Indians were then mutilated by some of the troops.

It was thought that Chief Niwot was mortally wounded and died a few days later. Although no exact statistics exist on the number of people killed during the Sand Creek Massacre, most historians believe it was approximately 180 people, most of whom were women, children and the elderly.

The Sand Creek Massacre was such an atrocity that President Abraham Lincoln, though occupied with the Civil War, called for a Congressional investigation into the tragedy. Congress ruled the “gross and wanton” incident a “massacre” rather than a “battle.” Chivington, who had publicly celebrated his “great victory” over the Indians was censured for his actions and lost his commission. Governor Evans was removed from office and Colorado was placed under martial law.

This massacre was one of the precipitating events that led to escalated Indian Wars throughout the American West.

The Sand Creek Massacre site is now designated as a National Historic site.

Stripped of their land, their culture, and their freedom, the Indians were ultimately forced to live on reservations. The Treaty of Medicine Lodge, signed in 1867, placed the southern Arapaho and the southern Cheyenne on a Reservation in Oklahoma.

Another younger Arapaho Chief, who lived in Oklahoma, was named Niwot in Left Hand’s memory.

The northern Arapaho were forced onto the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming, along with their hereditary enemy, the Shoshone. However, they continued to resist white settlement.

On June 25–26,1876, the Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes led by several major Indian war leaders, including Crazy Horse and Chief Gall, defeated General George Armstrong Custer and the 7th Cavalry Regiment of the United States Army in an overwhelming victory, during the battle of the Little Bighorn River. It was the most prominent action of the Great Sioux War of 1876, which had resulted from the growing animosity between the Native American inhabitants of the Great Plains and the encroaching settlers.

Throughout Boulder County, many places are named after Chief Niwot and the Arapaho Tribe. Names of the town of Niwot, Colorado, Left Hand Creek, Left Hand Canyon, Niwot Mountain, Niwot High School, Niwot Elementary, Niwot Ridge, Arapahoe Road in Boulder, and the Left Hand Brewing Company all pay tribute to Chief Niwot.

Valmont Butte, which is just east of present day Boulder, Colorado is a sacred Arapaho site where rituals and ceremonies were once performed. An Arapaho sweat lodge still exists there today.

This story provides a brief overview of the history of Chief Niwot, the Arapahos, the survival of the Plains Indians, and the Sand Creek Massacre. It was edited by Mel Fenson from information obtained from web sources and Margaret Cole’s book, “Chief Niwot.”

For more detailed information, read Margaret Cole’s excellent book. A well known Boulder author, Cole has conducted primary research into Niwot’s history and that of the Southern Arapahos. Her book is well written and thoroughly documents the events that led to the Sand Creek Massacre, subsequent government investigations into its causes, and the consequences that followed.

Special thanks Colorado photographer, Chuck S. Goode for his photos of Colorado Bison, Valmont Butte and the Pawnee Grasslands.