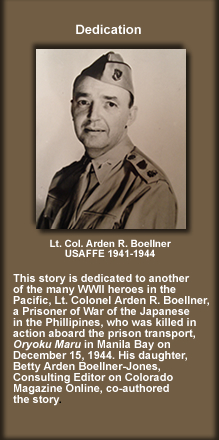

by

Betty Arden Boellner-Jones

with Mel Fenson

On Sunday

morning, at 7:58 am, December 7, 1941, carrier-based Japanese planes launched

a sneak attack on the United States Naval Base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, "A

day," President Franklin D. Roosevelt proclaimed, "that will live

in infamy." The United States of America declared war on Imperial Japan

the next day, vowing America would fight back with all her might, and win!

The

attack had been carried out by 353 Japanese torpedo bombers launched from

six aircraft carriers. They sunk four U.S. battleships, damaged four more,

sunk or damaged three cruisers, three destroyers, left 188 aircraft burning

on the ground, killed 2,402 military and civilian personnel and wounded 1,282

.

President Roosevelt, in January 1942, called upon his Chiefs of Staff for

a retaliatory air attack against Japan's heartland, Tokyo. A daring,

ingenious plan

was conceived. It was, something never before attempted. Could it be done?

The man chosen to lead the raid was Lieutenant Colonel James "Jimmy"

Doolittle, whose aviation and technical skills had caught the attention of

Army General "Hap" Arnold. Doolittle held a Ph.D. in Aeronautical

Engineering from MIT and had pioneered instrument flying. He was well known

for his daredevil flying escapades.

The

joint Army-Navy project was blueprinted and ready to be executed on

April 18, 1942. The plan: Sixteen B-25 Mitchell bombers were to be launched

from the aircraft carrier USS Hornet 400 miles from the Japanese

mainland, bomb military and industrial targets in Tokyo, Yokahama, Nagoya,

Osaka, and Kobe, then land in China. The initial concept for the attack had

come from Navy Captain Francis Low, Assistant Chief of Staff for anti-submarine

warfare, who reported to Admiral Ernest J. King that he believed twin-engined

bombers could be sucessfully launched from an aircraft carrier. Subsequent

short takeoff tests indicated that

it was possible.

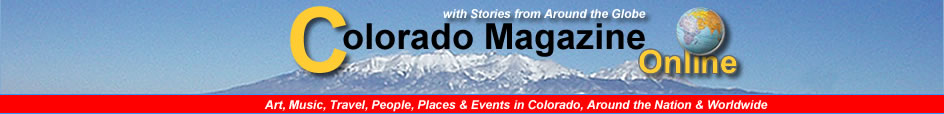

The newly commissioned USS Hornet, a 20,000 ton aircraft carrier

of the Yorktown class was big, fast, and ready with a crew of 2,200, but she

only had 500 feet of deck from which to launch the B-25 bombers.

Sixteen

North American Medium twin-engined bombers were chosen for the raid by LTC

Doolittle because of their range and bomb load capability. They could maintain

a speed of of 300 miles per hour at 15,000 feet, carry a bomb load of 2000

lbs., and 1100 gallons of fuel for a range of 2400 miles. Twenty-four of these

bombers were obtained from the 17th Bombardment Group, with six additional

planes for back up.

Doolittle originally suggested that the bombers might land in Vladivostok,

Russia, which would shorten the flight by 600 miles. Negotiations with the

Soviet Union were unsuccessful, so the plan was made to head 1200 miles east

to the China coast after the bombs were dropped. This made fuel limitations

critical.

The bombers received modifcations for the raid: rubber-sealed fuel tanks were

installed in the fuselage and the bottom turret was removed to provide space

for a 60 gallon fuel tank. The additional tanks increased fuel capacity by

an extra 440 gallons, enough to add 500 miles to bomber range. The Norden

bombsight was removed and a simplified sight designed by Lt. Ross Greening

was installed instead.

The bomb load consisted of two 500 lb. demolition bombs, approximately 1000

lbs. of incendiaries, a special load of 50 caliber ammunition, along with

a tracer, two armour -piercing shells and three explosive bullets. Additionally,

two broomsticks painted black, were installed in the tails of the bombers to

give the appearance of machine guns.

The lead ship and each of the flight leader's ships were equipped with electrically

operated automatic cameras which would engage when the first bomb was dropped.

Ten bombers carried 16mm movie cameras. Other special equipment, emergency

rations, canteens, hatchets, knives, pistols, and maps, were made secure before

take off. Preliminary training procedures were carried out before the mission

was set, under

the supervision of Navy Lt. Miller, at Eglin Field, Florida.

Training

was concentrated on short distance takeoffs, cross country flying, and night

flying. To accustom pilots and

navigators to flying without visual or radio references or landmarks,

navigation training flights were made over the Gulf of Mexico. Low altitute

approaches to bombing land and sea targets, rapid bombing and evasive actions,

and the bombing of targets at 1500, 5000, and 10,000 feet were also practiced.

Extensive range and accuracy tests were performed with gunnery, and at least

one practice carrier take-off was made by each pilot.

Each five man crew consisted of the pilot, co-pilot, bombardier-navigator,

radio operator and gunner-mechanic. All navigators were trained in celestial

navigation. Two ground liaison officers were assigned to each crew,

one on the mainland, the other on the carrier.

After their training was completed at Eglin Air Force Base, all sixteen B-25

crews were ordered to report to Alameda Naval Station in California. The bombers

and their crews were loaded aboard the USS Hornet on April 1, 1942.

Some of the crews had come with their planes from the 17th Bombardment Group,

others had volunteered for this highly secret and dangerous mission.

They sailed beneath the Golden Gate Bridge into the Pacific Ocean on

April 2, 1942, to join Admiral William F. 'Bull' Halsey's battle group and

sail toward Japan. The convoy was led by

Halsey's carrier the Enterprise and her escort of

cruisers and destroyers. The Enterprise's fighters would provide

protection for the entire task force in the event of a Japanese air attack,

since the Hornet's fighters were stowed below decks to allow the

B-25s to use the flight deck.

The attack plan called for the American bombers to be launched 400 miles from

Tokyo, then fly up waterways from the southeast and return in the same direction,

setting courses for several airfields in China, where they would refuel, then

fly to the Chinese air base at Chunking, about 800 miles further. The Chinese

were to be advised American bombers would be landing there after their raid

on Japan, but they would not be notified until shortly before take off to

prevent the Japanese from finding out about the impending mission.

Much planning was given to the best time and method of attack. It was

decided to take off just before dark and bomb targets at night. Doolittle's

plane was to take off ahead of the others, arrive over Tokyo at dusk, drop

its bombs, and light the targets for the other planes to follow.

After

the raid, the B-25s would head to landing points in China

to refuel, then fly to Chunking for arrival before dark. Radio silence would

be maintained throughout the flights.

Spirits were high aboard the Hornet as she steamed her way toward

Japan. Training aboard ship was intensified with briefings by Navy Lt. Stephen

Jurika Jr., and first aid and sanitation instruction by Flight

Surgeon, Lt. T.R White. There were also more lectures on gunnery,

navigation and meteorology and a procedure briefing by Doolittle.

All

pilots were assigned their objectives: steel works, oil refineries,

oil tank farms, ammunition dumps, dock yards, munition plants, and airplane

factories. They were also given secondary targets in case it was impossible

to reach primary ones.

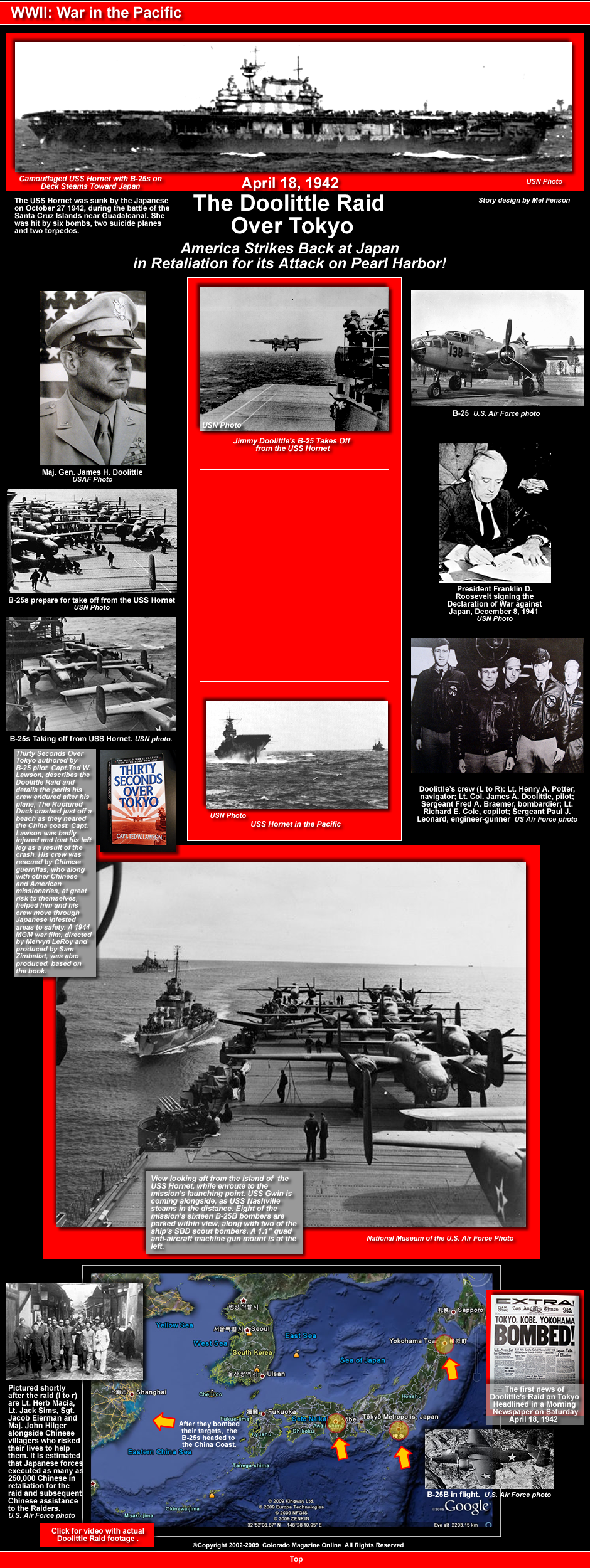

Each flight was assigned a specific course and coverage. The first flight of three planes led by Lt. Hoover covered the northern part of Tokyo. The second flight led by Captain Jones covered central Tokyo. The third flight led by Captain York covered southern Tokyo along with the north central part of the Tokyo bay area. The fourth flight led by Captain Greening would bomb the southern part of Kenegawa, Yokahama and the Yokasuka Navy Yard. Flight five would bomb south of Tokyo, proceed to Nagoya , where the flight would separate to bomb Nagoya, Osaka, and Kobe.

Final instructions were to avoid non-military targets and proceed as far West as possible after the raid, land on the water if the fuel ran out, launch rubber boats and sail in to the China coast.

The

attack was spread over 50 miles to

provide the greatest possible coverage,

create the impression that there was a larger number of airplanes than actually

used, and prohibit the possibility of more

than one plane passing any given spot on the ground to assure the element

of surprise. Low

altitude bombing, clear weather over Toyko, careful and continuous study of

charts and target areas were expected to assure successful results.

All was in readiness as the actual date for the mission moved closer. Unexpectedly,

at 3:10 a.m. on the morning of April 18, 1942, the first enemy patrol boat

was sighted, with a second Japanese boat appearing after daylight accompanied

by a third. The patrols were sunk by the Hornet's gun crews, but

it was believed that at least one radio message had been transmitted

to shore.

Early enemy contact created an emergency situation and Doolittle made the

decision to launch his B-25s immediately, even though the Hornet

was still a day away from the planned launch position and over 600 miles from

Japan, instead of 400 miles as expected. Fuel limitations would further heighten

the risk, but it was one his squadron must take.

Doolittle's plane was the lead bomber, taking off from the pitching deck of

the Hornet with only one-third of the normal distance required for

B-25 takeoff clearance. The other planes would follow to the

coast of Japan, flying at

barely 30 feet above the water to conserve fuel and evade

defensive detection. They would climb to 1200 feet to bomb their targets,

then fly on to emergency Chinese airfields.

Several of the bombers encountered anti-aircraft fire from Japanese guns,

but none caused severe damage. This proved that the Japanese were taken by

complete surprise.

The

relatively few fighters encountered during the attack indicated that Japanese

home defense had been reduced in the interest of making the maximum number

of planes available in active theaters throughout the Pacific. The remaining

pilots appeared inexperienced and in some encounters did not even attack.

The fire of the pilots that did actually attack was very inaccurate.

Communications between the US Navy and Chunking were finally made after the

premature takeoffs, but no radio homing facilities, light beacons, or landing

flares were provided at Chuchow. This, together with worsening weather

made safe landings after the raid impossible. None

of the planes reached the Chinese airfields. All the crews,

except one, either crash landed near the coast or bailed out into rugged Japanese

occupied territory. Two

crew members were killed bailing out.

One crew landed in Russia and was held until the duration of the war.

With the help of friendly Chinese, most of the fliers were able to evade capture and eventually make their way to Chungking where US military flights returned them to US soil. Several of the Doolittle Raiders remained in China to fly with Major General Claire Chennault's famous, "Flying Tigers."

Of

the eight crewmen captured by the Japanese, three were executed, five were

given life sentences, one died of starvation during imprisonment. In August,

1945, after 40 brutal months at the hands of their captors, days of torture,

starvation, solitary confinement, American troops arrived to liberate them.

Retribution by the Japanese against the Chinese civilians and missionaires

who had aided the Doolittle crews was horrific, with an estimated 250,000

of the populace killed.

The raid did not cause extensive material damage to the targets in Japan, but its success was in its daring undertaking and the tremendous morale uplift it gave to our nation. Doolittle's raid turned the tide of war in America's favor, and proved to the world we could fight back and win.

Upon

his return to the US, Doolittle was promoted from Lt. Col. to Brigadier. General,

and received the Medal of Honor from President Roosevelt. He

was later promoted to Maj. General and

continued a distinquished career in the military.

As for the USS Hornet, the carrier that launched this famous raid,

she became a prime target for Japanese revenge against the attack on their

homelands. The Hornet survived the battles at Midway and the Solomon

Islands, but at the battle of the Santa Cruz Islands near Guadalcanal, she

was hit by six bombs, two kamakazis and two torpedoes, and sunk on

October 27, 1942, after a glorious and heroic time at sea. Later in the war,

a new Essex class carrier was commissioned and ordered to be named the USS

Hornet in honor of the historic ship that took the Doolittle Raiders

on their mission in April 1942.

Story sources: The Doolittle Raid by Carroll V. Glines, Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo by Capt. Ted W. Lawson, General James H. 'Jimmy' Doolittle Autobiography with Carroll V. Glines, Doolittle, Aerospace Visionary by Dik Alan Daso, Doolittle, Biography by Lowell Thomas and Edward Jablonski, Wikipedia and Other Web Sources.

B-25

sound track from film,

"Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo"